|

|

His life is a palette

"Communist” Newspaper, N 222 (14701) 23 of September,1982

|

|

I have ingrown my roots

in this land

“Urartu”

newspaper, N 5(60), April 1994

|

|

The legend-man

“Republic of Armenia"

newspaper, N 159 (1919) 25 August 1998

|

|

Thesis

and antithesis of Valentine Podpomogov

“Golos Armenii” N 46 (18401) 29 April 1999 |

|

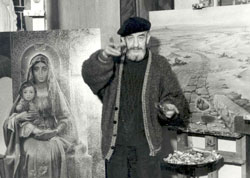

His

life is a palette

From the studio of an artist

The doors of his studio are always

open, but a question occurs for all the visitors - how do you get in?

It’s not that easy – to go in, without catching the

planks, leaning precariously against the wall and ready to fall on you

any minute, without turning over the buckets, without falling into the

hole in the floor, and finally without stepping on the cat, who bears

the grand sounding name Serapion. The cat follows your strange actions,

yawns, stretches himself and goes into the room. As usual, there are many

people inside, and th e

host, Valentin Georgievich Podpomogov, is telling one of his endless anecdotes,

which seems to be almost unbelievable. The guests' eyes are wet with tears,

and from time to time a burst of laughter shakes the walls of the studio.

And soon your laughter will be added to this. e

host, Valentin Georgievich Podpomogov, is telling one of his endless anecdotes,

which seems to be almost unbelievable. The guests' eyes are wet with tears,

and from time to time a burst of laughter shakes the walls of the studio.

And soon your laughter will be added to this.

Podpomogov is an artist, but saying that about him is like saying about

an astronaut: “he flies”. Because artists are different, and Podpomogov

contrives to be all at once: designer, film art-director, sculptor, architect,

and finally, painter. And as surprising as it is, all of these despite

the fact that he never obtained any relevant education. Life taught him.

He could write a novel named “My universities”, but he prefers the oral

tradition, and every listener wants to record his stories on tape.

Podpomogov was born in Yerevan in 1924 and has lived there most of his

life. He is a man, who grew up alongside with Yerevan, and as a real patriot

has a right to call the city his. He was the first artist of the city

and did a lot for Yerevan becoming the artist that we know and love now.

He was the first one who “revived” Armenian animated cartoons – he is

the creator of “A drop of honey”, “Parvana”, “The violin in the jungles”.

He created these as he says himself – on a “bare table”.

Now Podpomogov is more famous as a painter; his works are hanged in the

Museum of Contemporary Art. One can find out the impressions about his

art just looking in the visitors' book there.

His paintings are really stunning, with the depth of the thoughts enclosed

in them and the mastery with which it is delivered. The things happening

on in paintings are incredible and sometimes even severe, but they are

so convincing, that you think about them not as a possibility but as a

reality. By the way – that’s the principle concept of Podpomogov in art.

If you ask his opinion concerning what art must be like – he will say:

“convincing”.

“Expectation”. Nobody can stay indifferent to this woman, twisting her

slender fingers, pulling about the bandages on her hands. She doesn’t

have a face. Her expectation is faceless; it is a state, which everyone

knows. Faceless image and speaking hands – a paradoxical combination.

The painting touches the most innermost, the most concealed fibers of

soul in the observer's eyes.

The same is true not only for “Expectance”. All his paintings are paradoxical

and… convincing. It seems that there hasn’t yet been an artist, who co uld

deliver the horrors of war, the tragedy of a whole nation by painting

emptiness. Look at the “Requiem”. An almost empty space, bare earthcovered

with wreckage of stones, a sounding emptiness in the broken bell, and

only a tiny spark of light shimmering from the doors of a temple. A sinister

emptiness. uld

deliver the horrors of war, the tragedy of a whole nation by painting

emptiness. Look at the “Requiem”. An almost empty space, bare earthcovered

with wreckage of stones, a sounding emptiness in the broken bell, and

only a tiny spark of light shimmering from the doors of a temple. A sinister

emptiness.

There are not many of his paintings in the halls of museums, but it is

possible to tell about each of them for a long time, Podpomogov’s paintings

have the ability to stimulate thoughts.

Podpomogov can’t be called a fruitful artist. There are no canvases leaned

on the walls in his studio, no sketches and drafts, covering the floor

and the tables. There is one work on the easel, waiting to be finished

for a long time. And the author himself is busy making with enthusiasm

a palette of incredible construction and is as proud of it as he is with

the best of his paintings: “Leonardo didn’t have a palette like this”.

And nobody doubts that. And the mess is because the studio is under an

endless repair – because the host likes to make everything with his own

hands, inventing new constructions of incredible inventiveness.

-When do you work?

"Always. I am thinking. It is easy to paint a painting, when I totally

imagine it.

….And starts making a kind of chair, which nobody ever had."

Zara

Maloyan

"Communist" Newspaper, N 222 (14701) 23 of September,1982

|

|

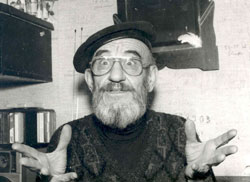

I

have ingrown my roots in this land

The

Armenian artist Valentin Georgievich Podpomogov will be 70 on 29 of April,

1994. A man of amazing destiny, he is very popular not only in the sphere

of artistic intellectuals. For many years Podpomogov’s jokes and phrases

are on lips of Yerevan. This interview is a kind of vis-à-vis –

allowing us to discover for us the famous master of cinema, brush, design,

to hear his thoughts about himself and time. The

Armenian artist Valentin Georgievich Podpomogov will be 70 on 29 of April,

1994. A man of amazing destiny, he is very popular not only in the sphere

of artistic intellectuals. For many years Podpomogov’s jokes and phrases

are on lips of Yerevan. This interview is a kind of vis-à-vis –

allowing us to discover for us the famous master of cinema, brush, design,

to hear his thoughts about himself and time.

- You are constantly turning to Armenian while speaking...

"My mother is Armenian, and though my father never spoke Armenian,

he understood the language very well -- 'I don't want to mar this gorgeous

language'" he would say. I am a native of Yerevan and when filling

in forms I write – nationality – Russian, mother language – Armenian.

I absolutely adore grabar, though do not understand it at all. I could

be creating my pictures in America or in Switzerland for example. But

that not what I need. I lived and worked in Paris for three months, and

though my mastery of painting was the same, something was wrong, perhaps

the alien ground under my feet.

One confession "I have a kind of crystal dream since childhood –

to create a series of paintings 'Silver suite'. The idea is - birth of

a human, his adolescence, youth, maturity, old age, death and ... birth

again."

"I started to paint to forget the earthly worries about a sunny and

warm place under the sun. Of course, I could be working somewhere abroad,

but there is one thing I understood: I will create this series of paintings

on the land, where I conceived the idea – in my homeland, in Armenia.

I have lived here so many years! I’ll see my seventies in April. My culture

is Russian, but through the prism of Armenia."

- You knew the great artists of this world, didn’t you? You were friends

with Martiros Sarian, with…

- I adored Sarian! He invited me to work in his studio, I refused the

invitation – “I will not become Sarian, and will loose myself”.

"I knew very well Kojoyan, Galenc, Hrachia Nersisian, Ervand Kochar…

So many unforgettable memories about them, sometimes funny ones. For example

I would always speak to Hrachia in Armenian, and he would always reply

me in Russian – I don’t know why. Imagine how it looked to people!

"Or Ervand Kochar visiting me one day – he came directly from the

scaffoldings of the monument of Vardan Mamikonyan. I was painting then

the picture 'Christ on his knees' (unfortunately it was stolen later).

And Kochar, knelt in front of the picture and said 'Gulo jan (that's how

he called everyone), do not even think that I knelt because you have created

a masterpiece – it's just my feet aching. I can't get up!'"

"I remember an interesting meeting with Papazian in Odessa, where

the film 'Heart of the poet' was being shot. Once, at one in the morning,

he knocked at my door (we had neighboring rooms in the hotel). We were

drinking cognac instead of tea – they have the same color. One bottle,

then the second one!"

Intuitively I always feel the artificiality - the real and the acting.

“I do not envy the kings, I have experienced being one on the stage –

confessed Papazyan – there is only one thing that I am envious of – Hrachia’s

talent”,- and started to sob. Next day during the shooting he didn’t greet

me, and he never did again: he couldn’t forget that he gave himself away

in a moment of weakness.

Paradjanov? He did an honor to me, suggesting to be the art director of

his “Color of Pomegranate” film. And what do you think? I said - no: “Serezha,

I love you too much to be working for you. You’ll be rude with me - and

I hate that. And there won’t be a film in the end”.

He was an extravagant person, I have never seen anyone of his kind in

my life. It was him that I loved truly.

How can I forget Paruyr Sevak with his thick and kind lips? Did you know,

that it was him who translated my name into Armenian - Entaognakanian

(literal  translation

of Podpomogov – “sub-helper”). translation

of Podpomogov – “sub-helper”).

I am not afraid of repeating myself by saying, that everyone must be doing

his job well. I am illiterate, I can't make out my handwriting myself.

I was expelled from the school, and never studied anywhere else. I became

a cartoon maker, because there was nothing else I could do then. But I

do not like cartoons, though made them for half a century. My credo is

– do everything as best you can. Even if do not do anything.

I was painting from early childhood, and I owe for that to one person

– Henrik Igitian. We both loved Her – the Art of Painting.

Yes, talent is a heavenly given gift, but you must work hard on yourself

as well, self education is a great thing. When I was working on my painting

“Mea culpa”, I had to go into thorough study of history of Egypt, culture

of ancient Maya. Creating “The Last Supper” would be almost impossible

without knowing well the Holy Bible. I am a believer, but not pious person.

I don't hide that I loved madly – as an addict – the cinema. But if I

was to start everything from the start – I would go to the theatre. It

is much more interesting, because the painter has to express with very

few means the idea, the spirit of the performance. In cinema the technical

means prevail, but theatre is more of a creative work. What a wonderful

feeling of relaxedness and creative enthusiasm I had when working on stage

production born by the genius of Vardan Adjemian and Hrachia Kaplanian.

-But there is also Podpomogov-sculptor, Podpomogov –designer...Hard to

keep up with the multiple expressions of your talent....

-You are right. This original frame for the painting I made myself (it

is the part of the whole idea), the copper fireplace in my house is also

made by me. The leather hat on my head is again of my own production.

I remember once in post-war Moscow, I had to make a coat for myself...

for the first and the last time  in

my life! in

my life!

I am also an applied-designer. Lamps, doors, fireplaces do not take much

efforts from me to make. It's lucky that I don't know neither physics

nor mathematics, otherwise I would be an aircraft designer too. I say

this without boasting. I really created with my own hands a beautifully

designed compact film developing device, I’ll show it to you when we are

done with the interview – it is under the stairs. I spent a year on it

– learnt metal turning. The main engineer of the cinema studio Eprem Roudman

died – never having believed that I made it myself.

-The artist paints in burst of inspiration, people admire his works, perceiving

them each in the boundaries of their intellect and spiritual quality.

Could you please comment on some of your works.

-Well, look here. This is “Joker” - I associate the hero of the painting

with Gorbachev: he has destroyed everything, not having created anything

new. “Curtain” - it expresses in an allegoric way the attitude to art

(you see the eyes behind the stage) and to marionettes. Though there isn't

any attitude left now.

“Funeral of faith”, “Expectation” - we always are captives of expectations

– from birth till death. And now we live with thoughts – when is all this

absurdity going to end. In short, each work has a whole world in it, the

mood of the artists, his philosophical vision of existence, his urge toward

the perfection of the cosmic spirit. That's what the work “Modern Crucifix”

is about.

Interview

by Ida Karapetian

"Urartu"

newspaper, N5(60), April 1994

|

|

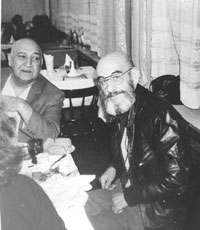

The

Legend-man

Dear

Maestro, I don't know you at all...

It was strange, it was unexpected – the artist and his paintings didn't

look similar at all, at least from the first sight.

People crossed the threshold of his studio with reverence. People would

go to the artist, expecting to meet a wise, gloomy, taciturn and secluded

person, who managed to find some time, a little window for you out of

his total business. You could see the amazement on their faces, when a

joyful, talkative man would appear in front of them - a master of telling

stories, communicative, with a great sense of humor, sometimes even light-minded.

He had elegant manners. He was an “artist” in the higher sense of the

word. It's hard to find someone who wouldn't like him after meeting him.

There would be a context felt – “you are interesting and important to

me, I don't know you, but you must be a good person. I do not care what

you think of me – but I want to do everything for you to feel good”.

Podpomogov had a unique, rare merit of spiritual generosity. Anyone who

has gone into his orbit would be endowed with merits he could only dream

about. Women would be declared to be beauties, or at least – interesting

women. All the men would become intelligent, brave, and – all as one –

“great specialists”. All the artists would turn into talented and genius.

And we all felt, perhaps for the first time in our life, that we are really

granted with all this merits.  People

would even get overcome with arrogance of their outstanding virtues, but

then would be cured as soon as they understood that these are all his,

Podpomogov's real virtues and he is endowing with them everybody around

him, because he has so many of these, because people are looking at each

other as in a mirror – and see what they are themselves. Nevertheless,

there were some people, who never got cured of this arrogance... People

would even get overcome with arrogance of their outstanding virtues, but

then would be cured as soon as they understood that these are all his,

Podpomogov's real virtues and he is endowing with them everybody around

him, because he has so many of these, because people are looking at each

other as in a mirror – and see what they are themselves. Nevertheless,

there were some people, who never got cured of this arrogance...

He was not a righteous man, neither a saint, and nothing of human life

went past him. He was not an envious person, but couldn’t forget the painful,

hopeless childish envy of children, who had toys, normal food and paints.

He remembered that, and already an old man was trying to satisfy that

childish hunger. Money disappeared as it came – he was buying things in

enormous quantities - 5-10 of each- different instruments, strange screwdrivers

and drills, saws and pliers. Or several cameras – to be shooting from

different angles, and would start to remake, redo them… Bunches of brushes

were scattered as firewood all over the studio - “so that I don’t have

to wash them”. He could find antique things and start making them move

and rotate and slide.

He h ad

a passion to make something out of nothing. It was equally interesting

for him to create a chair and a painting, and he would spend the same

time, efforts and emotions on both. Then this unique chair could just

be all stained or broken. The painting could be gifted to some passing

acquaintance, though the Maestro knew the price of it quiet well, but

could gift it to anyone – depending on his mood. ad

a passion to make something out of nothing. It was equally interesting

for him to create a chair and a painting, and he would spend the same

time, efforts and emotions on both. Then this unique chair could just

be all stained or broken. The painting could be gifted to some passing

acquaintance, though the Maestro knew the price of it quiet well, but

could gift it to anyone – depending on his mood.

He never kept the sketches and initial

drawings, they were lost, disappeared, or sometimes stolen. He thought

that there was no sense to keep them, though he was a perfect drawer –

and his drawings were no worse than the paintings. If it wasn’t for his

wife, Asya, who managed to save and keep all she could, nothing would

be left now.

People – good and not very good ones, clever and not very clever ones,

sincere and guileful – were coming to him in an endless flow, as if there

was a power attracting them to him.

Levon Igitian said in an interview: “We owe him one, we didn’t manage,

we didn’t think that the time is limited, and we are late now”. It’s not

all true. People managed – many managed to give him their love, to give

him something, anything, bring joy, though many managed to bring pain,

trouble and even treachery.

It is the society and the government that were late. We lack the tradition

to show consideration to people, who are the heroes of national, city

mythology. We don’t have the official status of “national wealth”… So,

I think, the society will be always late to do something for people like

Podpomogov. Their death will always catch people by surprise. And only

after that, after feeling the emptiness from their absence, the society

will try to give them their due. But they will not need it anymore – so

we do it mostly for ourselves.

And different myths and legends have already woven around Podpomogov,

and these we need.

Zara

Maloyan, Arts critic

“Republic of Armenia" newspaper, N159 (1919) 25

August 1998

|

|

Thesis

and antithesis of Valentine Podpomogov,

or Anniversary without Him

For

Podpomogov’s friends, this day, 29th of April, was one of the most bustling,

unpredictable and cheery holidays during last 7 decades - to be precise

- 74 years.

His wife Asya was dropping from tiredness, relatives-helpers were hindering

each other in the kitchen, the rizenschnautser Harry, kicked out of the

living room because of bad behavior, was barking indignantly.

Guests were coming in an endless flow. As usual, there were not enough

chairs and vases for flowers. Someone was trying to rule over this gathering,

someone was playing an instrument, and someone was drinking. Puffs of

smoke and din were floating over the table.

The harsh faces were watching indulgently from the paintings created by

Podpomogov. Those who have seen Podpomogov's paintings know the solemnly

strict aura, which spreads around them and captures the viewer. The viewer

slows down his tempo, becomes silent, stops smiling, the best mood is

substituted by sorrow, the way that it does when entering a church – it

is a feeling of touching something superior, something that concerns the

earthy life only with one side of it, something that is in other space

and dimension.

I always thought that it is impossible to live, eat, smoke, and watch

TV beside these paintings, as it’s impossible to live in a temple or in

a museum: they are not compatible with everyday routine. Only him, the

creator of these, Valentin Podpomogov could reside in this atmosphere

without any consequences, reigning over his little kingdom. The time had

different pace, space distorted here. His fantasy, which couldn't endure

monotony, manifested itself in his studio, in endless alterations and

repairs of it.

He was a subtle artist feeling the deep tragedy of human existence, called

Maestro even by close people, holding a strange reconciliation of a mischief-maker

and mystifier, ever playing, despite the venerable age and frailties.

Decades, given to cinema and theatre were not lost on him – he transformed

any space he came in. He built decorations in his dwelling, made staging,

where his life was performed as a play.  I

tried to count one day the number of levels in his studio, and counted

five of them. "Six, not five" -corrected me Asya, when I expressed

sympathy with her: to lay a table she had to go up and down the stairs.

"He likes these". And there were motherly notes in the intonation

of her speech, which is used to indulge in sprees of her talented child

and be proud of him. I

tried to count one day the number of levels in his studio, and counted

five of them. "Six, not five" -corrected me Asya, when I expressed

sympathy with her: to lay a table she had to go up and down the stairs.

"He likes these". And there were motherly notes in the intonation

of her speech, which is used to indulge in sprees of her talented child

and be proud of him.

Stairs, banisters, caged doors, stained-glass hatches, cellar-bar, unfinished

fireplace, monograms and emblems on the ceiling – he would be half way

through his architectural fantasies when the next ones would capture his

thoughts.

It is not very comfortable to live in a space like this, but he never

led an ordinary, normal life. Everything was constantly changing around

him, the real essence of things and people was revealing. It felt like

falling out of time pace, living in a parallel world, being the real one.

In this purely play space nobody could play –you were confronted with

yourself and were finding out something unexpected about yourself. A well-bred

society member would turn out to be a complete scoundrel, and a person

with a fame of bad morality would perform merits peculiar to children

and saints. The younger people demonstrated proficiency, the older ones

– naivety. Animals behaved like people, but not the opposite...

That’s who Podpomogov was, reconciling in him the painter and the thinker,

the constructor and the workman, the generosity and thrift, gourmandize

and asceticism. Any pair of contradictions is mostly possible to find

in Podpomogov, as if he is a joint spot of thesis and antithesis. Time,

space, people would fall under the influence of his personality, transforming

and polarizing. Everything seemed to transform or even become absolutely

different.

This year he would be 75. He didn’t live to see his round date. That's

somewhat symbolic – he was not a “round” person – he had the tension of

sharp corners in him and eternal strive up to where there is no space

and time equals the eternity.

Zara

Ter-Akopian, Art-critic

“Golos

Armenii” N 46 (18401) 29 April 1999

|

|

Translated by Hehine Koshtoyan

|